All That is Solid, written by the (I believe?) pseudonymous Sam Atis, is one of my favourite blogs. It is consistently interesting while maintaining a particular understated style, in both form and content, that is pretty unique in the generally quite overstated world of online writing.

A big part of that understated style is Atis’ consistent subtle scepticism, a wariness about bold claims and big ideas that he manages to keep to without succumbing to the temptation of brashly identifying as a contrarian. Some specific examples might be ‘Why I Am Sceptical About “Luxury Beliefs”’ and ‘Is There Really a Gender Equality Paradox?’ (note the ambiguous titles!). And more recently, he’s been writing about general reasons to be sceptical in the same understated way: ‘Most advice is pretty bad’, ‘Persuasive Books are Less Enjoyable’, ‘The Case Against Public Intellectuals’.

And today came ‘Beware Interesting Ideas’, which I read as the capstone of this project: Atis laying out the highest-level philosophical perspective on his scepticism. I strongly recommend you read it. I also think it’s wrong. We should embrace interesting ideas, not be wary of them—that is where most intellectual progress comes from.

Atis’ argument

Atis’ conclusion is that interesting ideas are less likely to be true. And he’s got a fairly simple statistical argument for this. People will tend not to say things that are simultaneously boring and false—why would you bother saying something like that? So even assuming that truth and interestingness are independent variables, when we limit ourselves to things people actually say or that we might actually hear, there’s a kind of selection effect at play. And this selection effect produces a negative correlation between truth and interestingness in this sample: an idea being boring is evidence that it’s true, and so (conversely) an idea being interesting is evidence that it’s false.

This effect has been noticed in other domains before: Atis mentions university students, where there’s a negative correlation between work ethic and intelligence, but only because people who are unintelligent and lazy don’t go to uni in the first place. You can see that in the graph below: the relationship between work ethic and intelligence is mostly random, with the big exception that the bottom-left triangle (representing people who score low on intelligence and work ethic) is completely empty. And because of that, the overall correlation is negative: if you find someone who is intelligent, they are more likely to have a relatively low work ethic, and vice versa.

We might imagine a similar graph plotting interestingness against truth. Overall, a graph of all possible ideas would look pretty random, and there would be no correlation. But if we limit ourselves to thing that people actually say, we would cut out the bottom-left triangle of things that are false and boring, and so truth and interestingness would be negatively correlated. And so, if you come across someone saying something interesting, you should for that very reason downgrade your estimate of its truth.

I have two main problems with Atis’ argument. The first is that I think there’s reasons to be wary of it on its own merits; the second, more fundamental, problem is that even if Atis were right, we should still seek out interesting ideas even knowing that they’re less likely to be true.

Humans are stupid, and your friends are interesting

Atis’ core premise is that people will tend not to say boring-and-false things. This seems to me to be totally incorrect. Last time I got my hair cut, I got a really chatty barber—something I already hate—who insisted on making the most boring small talk about the city. But, even worse than that, he got everything wrong! He said the Rossville flats were demolished in the mid-90s (the actual date was 1989) and remembered the Peace Bridge being opened more recently than it was.1 The conversation was simultaneously incredibly boring (especially given that the history of Derry is actually super cool) and extremely infuriating: the barber was making a load of boring-yet-false claims. Of course, it wasn’t his fault, and he probably sincerely believed these things; but they were false nonetheless.

People rarely intend to say boring and false things. But people are incredibly bad at knowing what’s true and what’s false, which means that even with this good intention they probably do often say things that are simultaneously boring and false. If we start with a graph plotting interestingness against truth for all ideas, and then cut out the things people won’t actually say, we’re not actually just cutting out the bottom-left triangle: we’re cutting out a relatively random selection of points based on their perceived truth. On this account, truth and interestingness will still be negatively correlated, because perceived truth is still correlated a little bit with actual truth (humans aren’t that stupid). But the negative correlation will be extremely weak, and if we come across an interesting idea that seems otherwise true, thinking about this correlation should only downgrade our credence in it a tiny bit.

Indeed, I think there’s a much more important selection effect that Atis doesn’t mention. We tend to surround ourselves with people we find interesting, and we like having conversations on interesting topics. People who we think are boring, or with whom we just don’t share many interests, tend to be the people we drift apart from, mute on twitter, etc. And so, while the people around us probably won’t say many false-and-boring things, they probably also won’t say very many true-but-boring things either. And for this reason, there would no longer be a correlation between truth and interestingness: an idea being interesting would give you no information about its truth. The graph of ideas we actually hear would have the entire bottom section of genuinely boring ideas cut off, and the negative correlation would disappear.

Truth is boring

That’s the reason I think Atis’ argument is wrong. But I get the sense that he and I have a deeper disagreement: I think that even if his argument were correct, and an idea being interesting were evidence against it being true, we should still embrace interesting ideas.

Truth is a binary property: true or false, one or zero, no other possibilities. When ranked on the scale of truth, there is no distinction between any true idea and 1+1=2. And importantly, there is no distinction between any false idea and something as silly as 1+1=3. Something like Newton’s law of universal gravitation, which is strictly false and has been superseded by general relativity, is indistinguishable from ‘cows go baa’ on the scale of truth.

We might try to create some kind of sliding scale where ideas can be closer to or farther away from the truth even if they’re strictly false. But ultimately, this scale would still have the problem that nothing could be truer than logical tautologies like ‘everything is the same as itself’ or ‘if something is true, then it’s true’. The scale of truth maxes out at some point, and most of the things that are at this maximum are pretty boring. In this way, truth is a trivial property.2

Thus, a writer who only cared about their ideas being true would not be out reading papers, evaluating evidence, listening to arguments, or reading books. They would sit alone, in a room, uploading a series of posts that looked like the following:

‘1 is odd’

‘2 is even’

‘3 is odd’

‘4 is even’

‘5 is odd’

‘6 is even’

…

Such a writer would only ever write about true ideas; and because eventually the numbers would get big enough that no previous human would have ever had reason to say whether they’re odd or even, if they kept at it long enough they’d end up producing genuinely original ideas that nobody had produced before. But nobody would care. The ideas that this writer would post are true, but they’re all trivial.

Seek important truths

The reason we care about ideas being true is typically because they might capture something important. We care about whether or not a bit of political science research is true because it might capture some important truth about our politics; we argue about truth in ethics because of the impact it might have on how we understand ourselves and our values; we worry about the truth of our physical theories because of how they affect our understanding of the world we live in.3

But in order to capture something important, ideas typically have to be interesting. Or, to put it another way: if you want to find out important truths, you should seek out interesting ideas. Bold, brave, exciting ideas are typically exciting exactly because they would tell us something important if they were true. This is not universally correct (interestingness is pretty subjective, so some genuinely important ideas can seem boring to some people, while others are obsessed with totally meaningless claims), but the correlation is very strong. If you want to genuinely change your mind—not just gain a new thought that might be as trivial as ‘48 is even’, but genuinely alter how you see the world—you must chase interesting ideas.

Indeed, you should seek out interesting ideas even if the ideas in question are false. To be sure, coming to believe an interesting-but-false idea can be dangerous; but entertaining the idea, turning it over in your mind and trying to reason as if it were true, is one of the most powerful ways to discover other important truths. For example, the Efficient Market Hypothesis is probably not exactly true as originally stated (it is roughly correct and you almost certainly can’t beat the market, but the evidence for strong forms of the hypothesis is decidedly mixed); but a thorough understanding of it can change how you look at the world, giving you a new perspective on how society can get stuck in coordination problems and when it’s possible to break out of that equilibrium.4

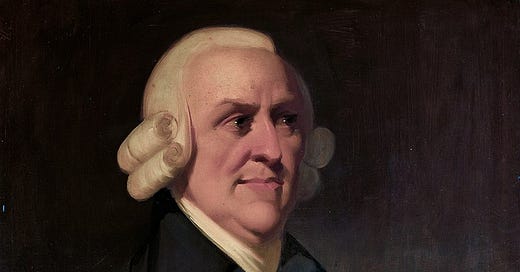

I think this is where most intellectual progress comes from. Over time, received opinion tends to stabilise into an ossified paradigm, and these paradigms tend to remain stable even as they run out of steam and stop making important new discoveries. For long-term intellectual progress to occur, there needs to be some new idea or set of ideas that upsets the whole way of thinking on a fairly regular basis. In some cases, these ideas are true: Adam Smith’s ‘very violent attack … upon the whole commercial system of Great Britain‘ was all the more powerful for being correct. But in other cases, this external impetus is completely false, but nonetheless thinking it through generates powerful intellectual progress. Freud’s psychoanalysis led to new questions being asked about the conscious mind, decision-making, health and illness, and even science itself, despite mostly being bullshit.

If we were overly wary of these paradigm-shifting ideas (which tend to be the most interesting!), we would fail to make proper intellectual progress either at an individual or collective level. If we are wary of interesting falsehoods, we might end up with true beliefs; but to paraphrase John Stuart Mill, these beliefs will be dead dogmas, not living truths.

None of this is to say that we should drop our critical thinking faculties when confronted with something that would be ‘huge if true’. Indeed, I take it to be one of the great services of sceptics like Sam Atis to hold in check our natural tendency to get overexcited by shiny new things, and pull us back down to the ground. But while this natural tendency is bad, I feel that the opposite tendency to be wary of interesting ideas would be even more dangerous. We should engage with and seek out interesting ideas, even if they are more likely to be false.

I think Sam Atis’ excellent post, despite taking the opposite position, is ironically a fantastic example of this. I believe it is false, but it is nonetheless incredibly interesting, and I think you should all go and read it.

Yes, I haven’t got my hair cut since moving to Cambridge. I make no apologies.

A response might be that I’m being uncharitable: Atis wouldn’t want to define the sliding scale of truth so that it became trivial in this way, and so I shouldn’t impose this trivial definition on him. But as it turns out, there is a relatively lively area of philosophy of science where Karl Popper and a bunch of his followers have been trying to define a non-trivial numerical measure of ‘truth-likeness’ for over half a century, and my impression is that the general verdict of the rest of philosophy is that they have failed and there probably is no such scale. It’s worth reading the mathematical proof that Popper’s original attempt was a failure, which is all the more devastating because it came from someone so obviously sympathetic to Popper.

None of this is to say that truth is a merely instrumental value: my favourite resources for understanding the intrinsic value of truth in a non-maximising way are Huw Price’s ‘Truth as Convenient Friction’ and Bernard Williams’ Truth and Truthfulness. The idea that all values are either completely intrinsic and totally independent of other values, or completely instrumental and totally dependent on them, is another piece of silliness we have inherited from post-Sidgwick consequentialism—there’s never a bad time to read, or re-read, Anscombe’s ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’.

Unfortunately, the clearest example of this line of reasoning is Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Inadequate Equilibria, which is a pretty poor read.

Sp comprehensive it challenged my pre-noon consciousness even after two coffees and several hours on Twitter. Very little does that - congratulations!